A parasitic infection called onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness, is widespread in sub-Saharan Africa. After trachoma, it is the second most frequent infectious cause of blindness worldwide.

WHO considers onchocerciasis a neglected tropical disease (NTD). The world’s most endemic nation is Nigeria. There have been over 99% of documented cases of river blindness in sub-Saharan Africa. Yemen and Latin America are some additional locations.

By 2030, the WHO wants to completely eradicate onchocerciasis in 12 of these nations.

What Is River Blindness, and Why Does It Occur?

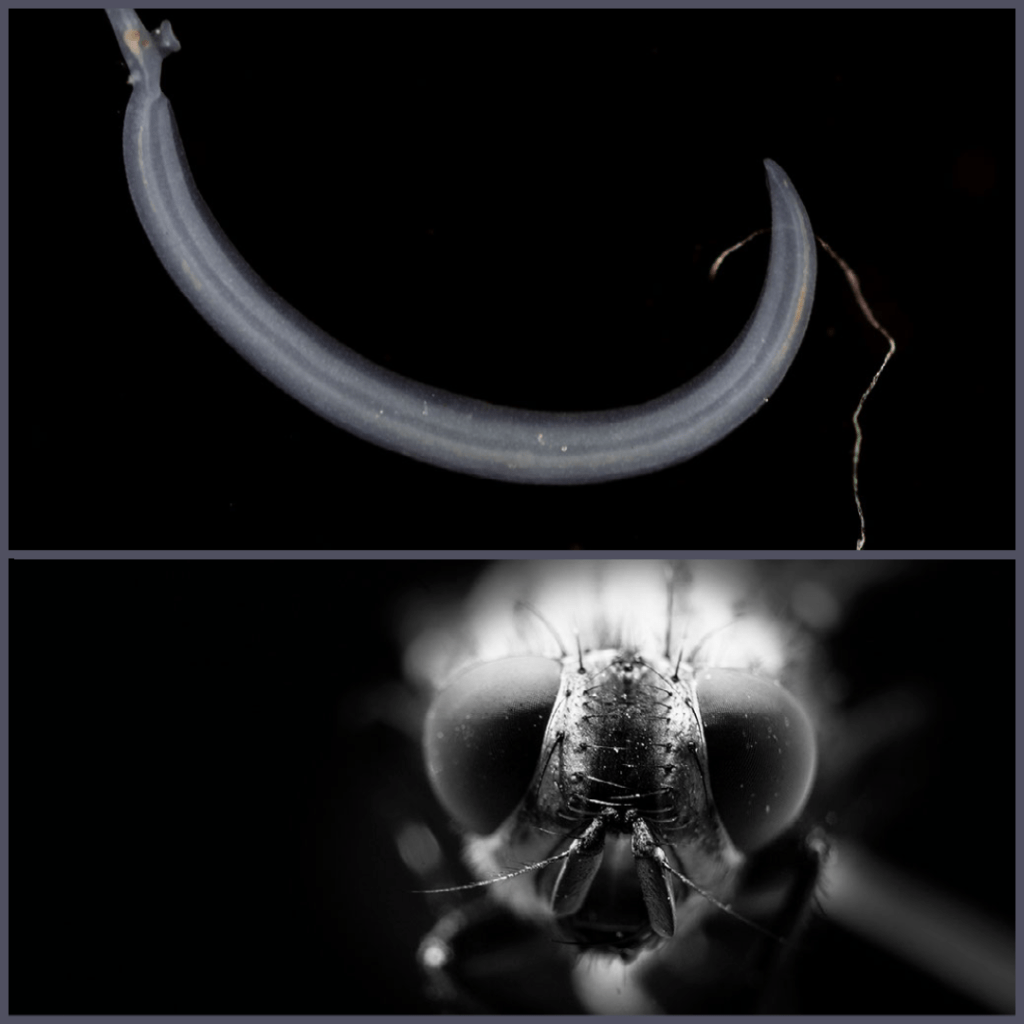

A parasitic worm called Onchocerca volvulus, transmitted by black flies biting during the daytime causes river blindness. Black flies breed in areas near rivers with rapid currents.

Female blackflies consume microfilariae when they feed on blood from infected people. It takes about one to three weeks for these microfilariae to grow inside the blackflies before they are passed on to their next human hosts.

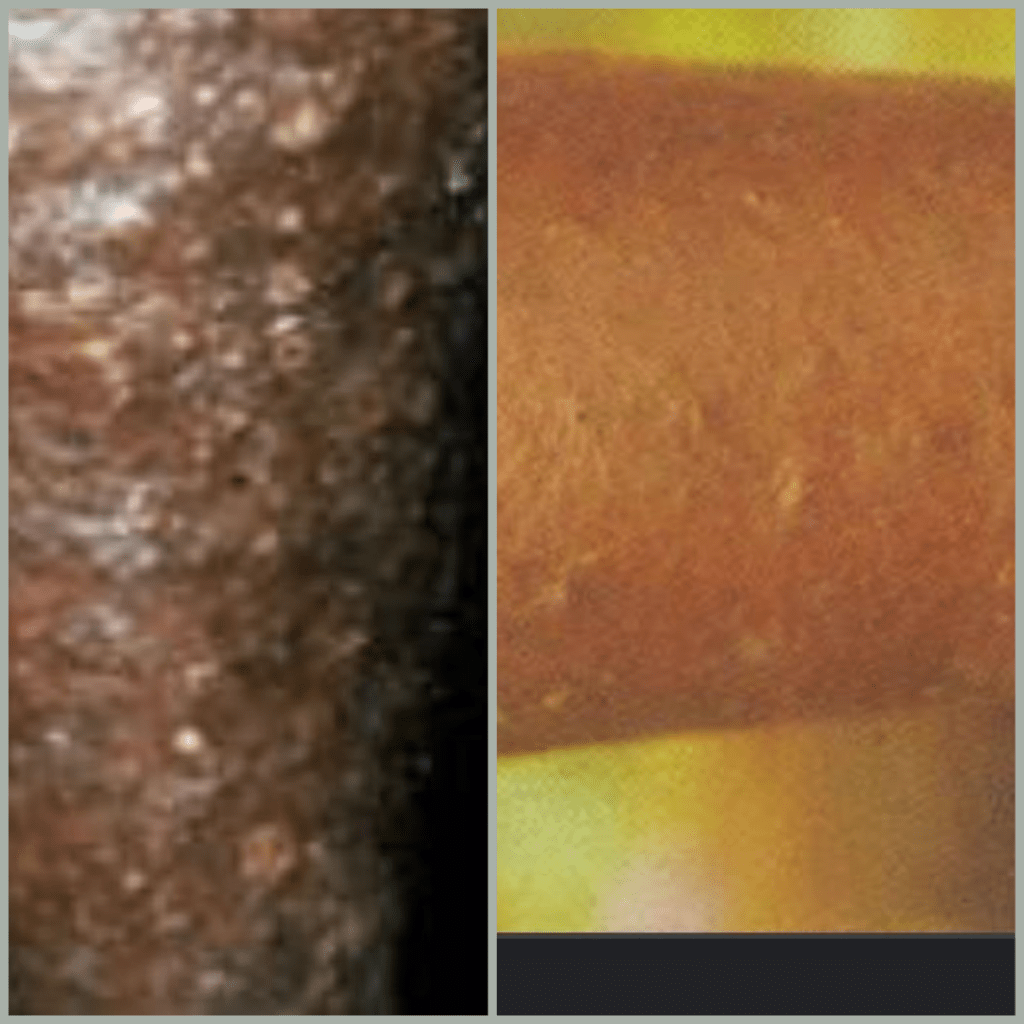

When an Onchocerca larvae-carrying black fly bites a person, the larvae enter their skin through the bite wounds and develop into nodules, where they slowly mature into adult worms over the following 12 to 18 months.

The adult worms travel throughout the body and feed on various bodily fluids as they live and reproduce there for over several years (10-15).

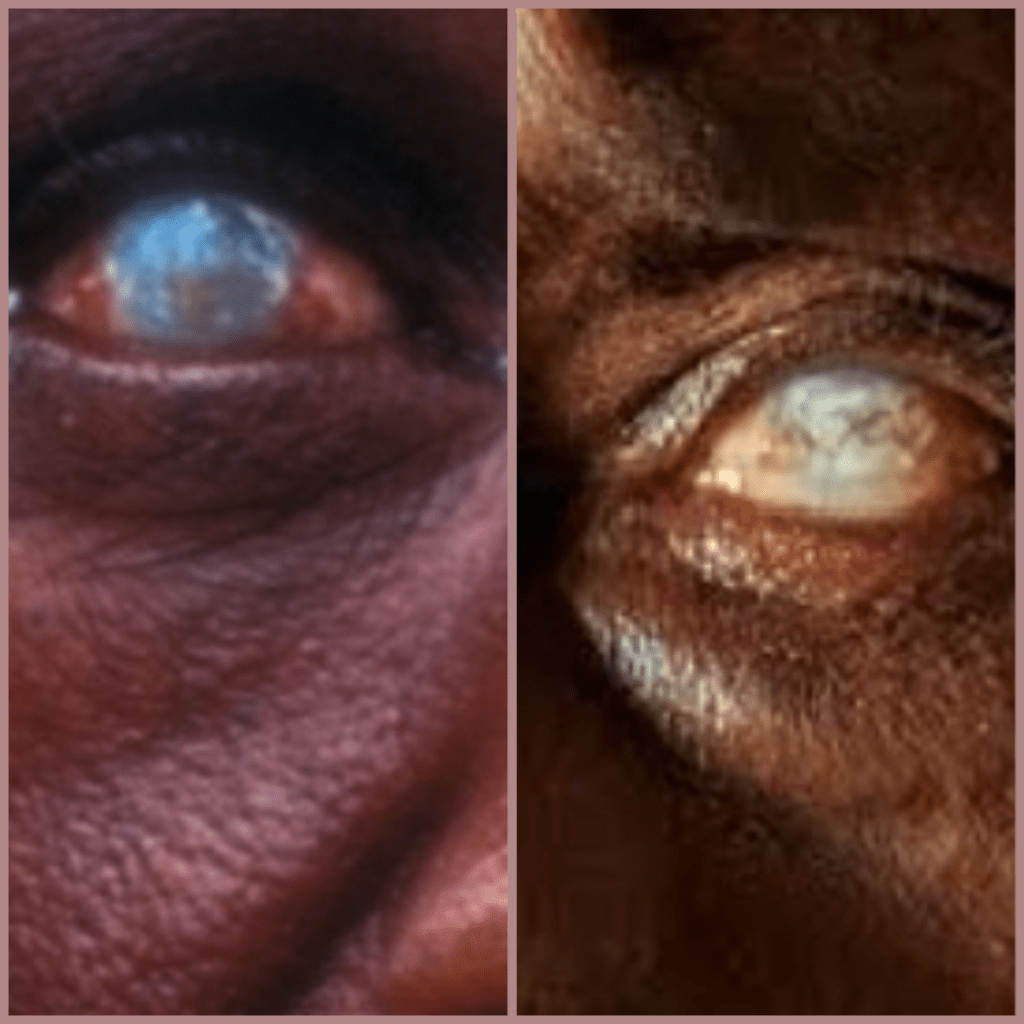

Microfilaria doesn’t cause much harm as long as they are living, and can be seen floating inside the eye. However, the dead larvae build up in the tissues of the eye and cause inflammatory reactions and scarring when they die. Ultimately resulting in vision loss and even blindness.

OCULAR SYMPTOMS

In the beginning, river blindness sufferers may not exhibit any symptoms at all. The symptoms are caused by dead larvae and the body’s immune response to them. Therefore, they may take a year or more to manifest and may become worse over time. The following eye symptoms may appear over a period of 10 to 15 years following the black fly bite:

- Cataracts

- Unusual growths on the surface of the eyes.

- Allergic reactions such as itching and watering

- Redness

- Sensitivity to light

- Vision loss

- In some severe cases, there can be glaucoma, corneal scarring, or retinal damage.

DIAGNOSIS

1. Skin snip: The skin snip is the most typical diagnostic technique. A small amount of skin tissue (1-2mg) is biopsied or shaved in order to identify the larvae.

Under a microscope, larvae emerge from shavings or biopsy (“skin snips”) put in physiological solutions (e.g. normal saline).

Typically, six snips are taken from different parts of the body.

2. PCR: Even if no larvae are visible under a microscope, PCR can still detect the infection.

3. Eye examination: A slit lamp examination is done to detect lesions and larvae in the eye.

TREATMENT

- Ivermectin is given every 6 months for at least 12 to 15 years to stop transmission of Onchocerca volvulus.

- Moxidectin: According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, it is more effective than ivermectin at killing the larvae of onchocerciasis.

PREVENTION

There is currently no treatment or vaccine available to stop river blindness. Therefore, avoiding areas with high infection rates is the best way to prevent river blindness. The CDC recommends the following precautionary measures.

- Using insecticides containing N,N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) on exposed skin,

- Wearing long sleeve shirts and pants, and

- Wearing clothes treated with permethrin can help you avoid getting bitten by blackflies.

- Avoiding fast-moving rivers and streams which is the breeding ground for black flies